Nard (نرد), originally called Nardashir (نردشیر), is a Persian game, which is played on a backgammon board. The modern backgammon and its variations originated with the Persian Nard. The earliest source to mention the game, Nardashir, by name, is the Babylonian Talmud (Ketubot 61b), in an anonymous statement, which is dated to the latest stratum of the Talmud, 500-600 CE.

However, the Talmud does not explain how to play the game.

According to some historians, such as Murray, the game Nardashir was possibly invented by the 3rd century Sassanian king Ardashir I. However, as I will point out from the sources it is clear that that is not true.

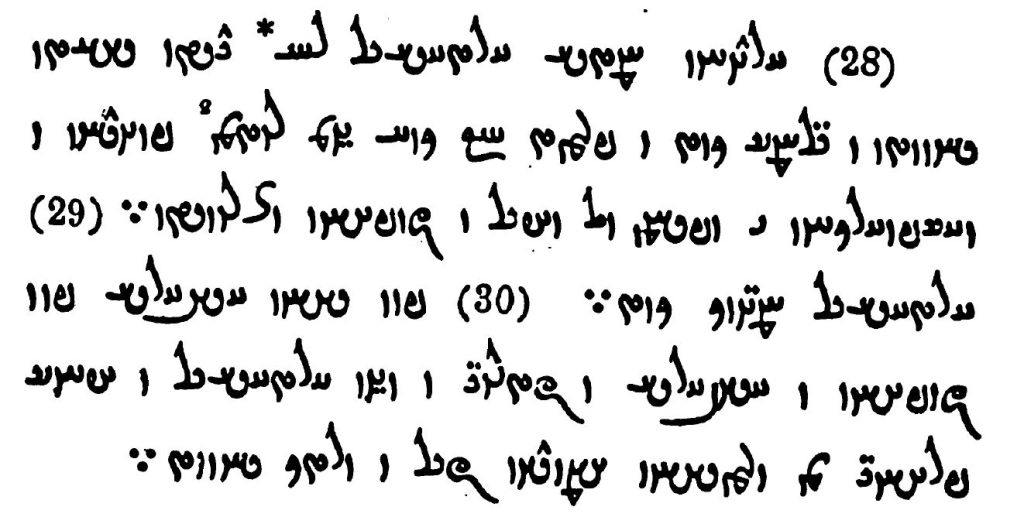

In a 7th century CE, Pahlavi work, called Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Papakan (کارنامهٔ اردشیر بابکان), Book of the Deeds of Ardashir, Son of Papak, (1:30), we are told that the Sassanian King, Ardashir I (reigned 224-241 CE), excelled at playing this game, while he was still a favorite in the service of the Parthian King, Ardavan (Artabanus) V (reigned 208-224 CE), implying that the game was already in existence in the early 3rd century CE.

When Ardavan saw Ardashir he was glad, expressed to him his affectionate regard, and ordered that he should every day accompany his sons and princes to the chase and the polo-round. Ardashir acted accordingly. By the help of Providence he became more victorious and warlike than them all, on the polo and the riding (ground), at Chatrang (Chaturanga chess) and Vine-Ardashir (Nardashir), and in (several) other arts.

Text and English translation from:

Sanjana, Darab Peshotan. The Karname i Artakhshir i Papakan: being the oldest surviving records of the Zoroastrian emperor Ardashir Babakan, the founder of the Sasanian dynasty in Iran; the original Pahlavi text edited for the first time with a transliteration in Roman characters, translation into the English and Gujerati languages, with explanatory and philological notes, an introduction, and appendices. Printed at the Education Society’s Steam Press, Byculla. 1896.

Many historians imply that based on this quote Nardashir was already known in the 3rd century CE. However, it is clear that this quote, written in the 7th century CE, is merely an anachronism due to the confusion between the game being named after Ardashir I as a tribute to him, and him actually playing it, as is explained in the main story of the invention of chess (Chaturanga or Chatrang) and backgammon (Nardashir or Nard), quoted next.

What seems to me is the more correct and realistic story of the invention of Nard, and therefore backgammon, is the story brought down in the 6th century CE Pahlavi work by the Persian Grand Vizier of the Sassanian emperor Khusro I, Bozorgmehr (Wuzurgmihr) (~498-590 CE), Wicarishen i Chatrang ud Nihishen i New-Ardashir, Treatise on Chess and the Invention of Backgammon, also known as Chatrang Nama. This book is short, consisting only of 39 verses, which I quote here in full, since it explains not only the history of both chess (Chatrang) and backgammon (Nardashir), but also the original rules on how to play them.

This story, written by Bozorgmehr himself, about how he invented Nard, also fits in great with the quote from the Talmud, being dated to the 6th century CE, because the Talmud used this brand new game at the time, as an example that was familiar to everyone, and probably the talk of the town, to illustrate a question regarding civil law. Analysis by Murray and Kess (see bibliography) who question the authenticity of this story is simply not adequate due to their lack of expertise in reading and dating the original Jewish Aramaic and Pahlavi texts and using poor translations.

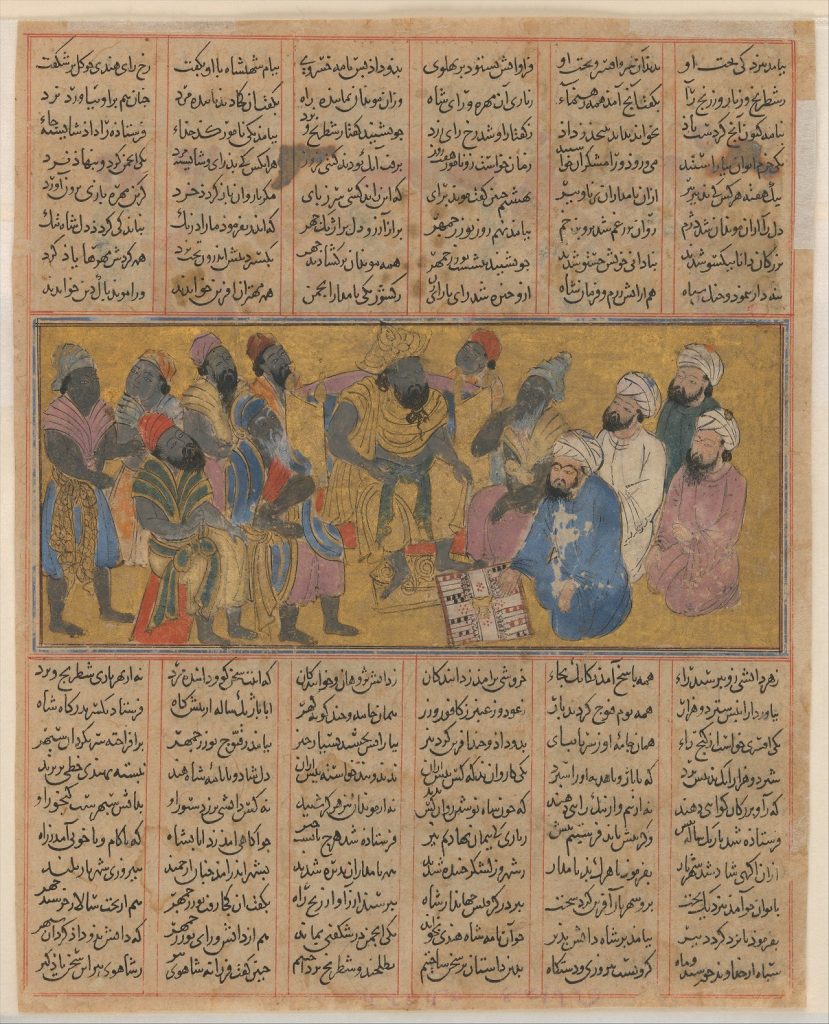

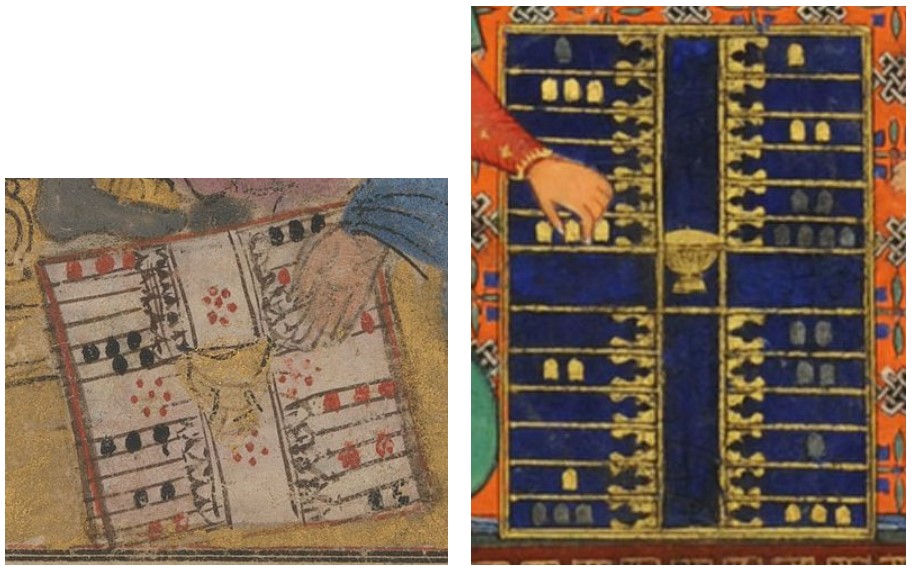

A later retelling of the same story about Bozorgmehr’s invention of the game, is recorded in the Persian epic poem, Shahnameh (شاهنامه), The Book of Kings, by the Persian poet Hakim Abul Qasim Ferdowsi Tusi (حکیم ابوالقاسم فردوسی توسی), written in 1010. Ferdowsi has somewhat different rules than Bozorgmehr, and seems to be describing a completely different game, which has 8 pawns and a king on an 8×8 board just like chess. This resembles a modified Roman game Ludus Latrunculorum with two dice, which I will discuss separately. However, in the illuminated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, the game drawn is always the classic Nard/Backgammon, just with a different initial setup than what we are used to. How the illustrators interpreted Firdowsi’s words and compared them to their drawings is not really well understood. It is clear that Firdowsi’s audience knew exactly what the game was, and probably assumed that he took a poetic license to describe it, thus making his description historically not accurate. I have left out Firdowsi’s description of Nard out of this article on purpose, to avoid confusion, and only have shown the drawings from some of Shahnameh manuscripts, which clearly show Bozorgmehr’s original game.

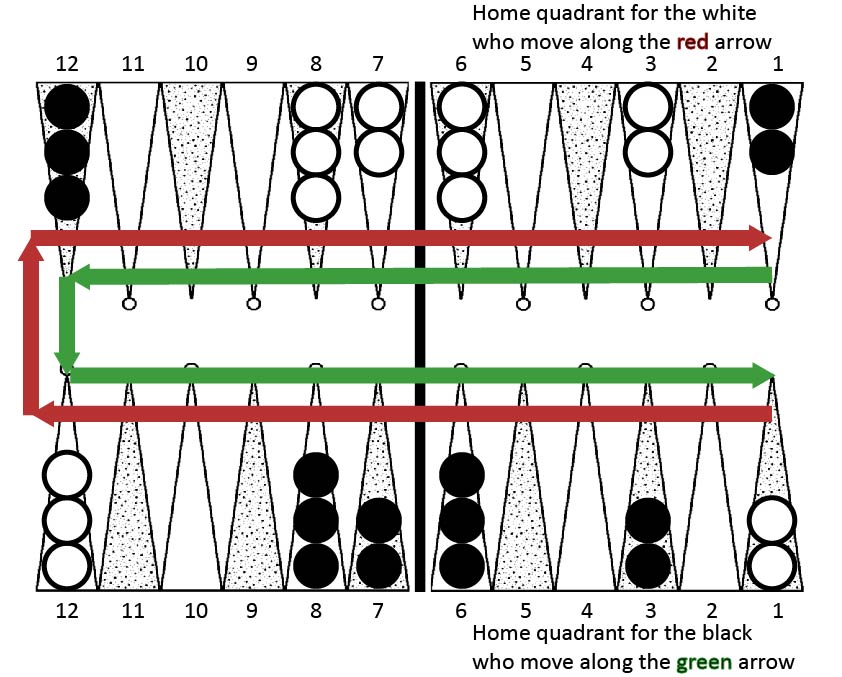

- The board is divided into 4 quadrants, because there are 4 elements from which everything was created.

- Each quadrant is divided into 6 lines, because first Ahura Mazda created 6 spirits (manifestations), or goddesses.

- 2 separate dice are used, one to represent revolution of the firmament and one to represent the revolution of the constellations.

- The checkers move in opposite direction from each other, since the white ones represent Ahura Mazda, the good god, who is opposed by Ahriman, the evil god, in all of his doings, represented by the black checkers.

- Spandarmad is Ahura Mazda’s manifestation #3, out of the total 6. Therefore 3 checkers are placed on line 6 (representing 6 creations including man), on line 8 (???), on line 12 (representing 12 constellations). 2 checkers, representing the primeval man and primeval bull, are placed on lines 1, 3, and 7 (representing 7 planets).

Single checkers can be hit and removed off the board back to the center bar to be re-entered into the game from the beginning.

Nard Rules

Original Nard Rules according to Bozorgmehr with some additional clarifications:

- The game is for two players.

- The game equipment consists of a board with 4 quadrants with 6 lines in each; 30 round checkers, 15 white ones for one player, and 15 black ones for the opponent; and two 6-sided cubic dice with numbers 1-6 on it.

- The initial position of the checkers for each player is on lines 1 with 2 pieces, and line 12 with 3 pieces, one one side, and lines 3 and 7, with 2 pieces, and lines 6 and 8 with 3 pieces, on the other side. The pieces move in the opposite direction of the opponent’s pieces around the board to the opposite 4th, home quadrant.

- To determine who which player goes first, each player throws one dice and whoever scores higher goes first. This throw does not count for the first move.

- To start moving, both dice are thrown together and the value on each dice is the number of lines each checker can move starting from line 1. There is no specific order in which the checkers have to move around the board. The player can move any of the checkers at any time.

- There is no limit to how many checkers of a player can be present on a single line.

- A checker can be moved only to an open line. If a line is occupied by 2 or more checkers of a player, the opponent is not allowed to land on it.

- The numbers on the two dice constitute separate moves. For example, if a player rolled 2 on one dice and 6 on the other dice, they may move one checker two spaces, and another checker 6 spaces. Or they can move the same checker 2 spaces onto an open line, and then move that same checker another 6 spaces onto an open line. The intermediate stop of the checker must not be occupied by two or more of the opponent’s checkers.

- Bozorgmehr’s rules do not discuss scoring doubles (same number on both dice), and therefore in this rule set there is no special double move.

- Moves are mandatory. If it is possible to make a move from both dice then the player must make both moves. If only one move is possible and the other is not then the player must make that one move. If neither moves are possible, then the player skips their turn.

- If a single checker is present on a line, then it can be hit by an opponent’s checker and removed off the board onto the center bar, back to the beginning of the game. If there are two or more checkers present on a line then they are safe and the opponent cannot land on that line.

- If the player has checkers sitting on the bar they must move them back into the game first, before moving any other pieces. The checker on the bar lands onto the line equal to the number of one of the dice rolls, as long as that line is unoccupied. The player may not move any other pieces, until all of the checkers on the bar have been reentered back into the game. The player must make a move on the counts of both dice. So if one dice was used to move a checker from the bar, then the second dice must be used for another checker on the board, or the same checker to move further down the line.

- The checkers can move off the board only after all 15 of them have arrived in the home quadrant first.

- Checkers can be hit onto the bar even inside the home quadrant.

Bibliography:

- Sanjana, Darab Peshotan. The Karname i Artakhshir i Papakan: being the oldest surviving records of the Zoroastrian emperor Ardashir Babakan, the founder of the Sasanian dynasty in Iran; the original Pahlavi text edited for the first time with a transliteration in Roman characters, translation into the English and Gujerati languages, with explanatory and philological notes, an introduction, and appendices. Printed at the Education Society’s Steam Press, Byculla, 1896.

- Murray, Harold James Ruthven. A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess. Clarendon Press, 1952.

- Keats, Victor. Chess in Jewish History and Hebrew Literature. Magnes Press, 1995.

- Tarapore, J. C. Vijârishn I Chatrang: Or The Explanation of Chatrang and Other Texts. Transliteration and Translations into English and Gujarati of the Original Pahlavi Texts with an Introduction by J.C. Tarapore. Bombay: The Trustees of the Parsee Punchayet Funds and Properties, 1932.