Roulette—literally “the little wheel”—is among the most enduring institutions of gambling and a touchstone for debates about chance, probability, and risk. Its history is not a single invention story but a convergence of wheel-based and number-betting games across the 17th and 18th centuries, consolidated into the numbered wheel and table layout that spread from late-18th-century Paris to 19th-century German spa towns and the Riviera, and then to the United States. This article provides a reference-grade account, grounded in historical sources, of how roulette emerged, standardized, and proliferated; why variants (single-zero vs. double-zero) diverged; how rules such as la partage and en prison change expected value; and how myths—Pascal’s “invention,” the “Devil’s wheel,” and legendary streaks—sit alongside the documentary record.

Scope and terminology. We use “European/French roulette” for the 37-pocket single-zero wheel and “American roulette” for the 38-pocket double-zero wheel. We distinguish wheel topology (how many pockets; the number order) from rules (settlement of even-money bets on zero, table limits, side wagers). We treat the most frequently cited precursors—Roly-Poly, Even–Odd (E.O.), Biribi, Hoca—before turning to the first unambiguous description of a modern roulette wheel in late-18th-century Paris, the single-zero innovation of the 1840s, the American double-zero tradition, and the game’s mathematical and cultural afterlife.

Thesis. The best-supported lineage is: Roly-Poly/E.O. (wheel with bank advantage) + Biribi/Hoca (number betting and bank reservation) → Paris, 1790s (numbered wheel with 0 and 00; modern layout attested) → 1840s single-zero standardization in the German spa circuit → 1860s–1900s Monte Carlo’s global prestige → American double-zero consolidation, later online variants, and occasional commercial “inflations” (e.g., triple-zero).

Early Precursors and Context (17th–18th Centuries)

Mechanical prehistory and the Pascal legend

The most persistent origin myth credits Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) with inventing roulette while seeking a perpetual-motion machine. What is documented is that Pascal’s correspondence with Fermat in 1654 helped found probability theory, sparked by questions from gamblers; and that 17th-century Europe teemed with mechanical curiosities—inclined planes, balancing wheels, and “philosophical toys”—that normalized the idea of spinning apparatuses as public entertainments. What is not documented is a numbered roulette wheel in Pascal’s time. The Pascal story is best read as intellectual prehistory: a reminder that gambling problems prodded mathematics, and that a culture of mechanical spectacle predated casino wheels.

Biribi (Italy/France): number betting with a heavy bank edge

Biribi—attested in Italy by the 17th century and spread into France—was essentially a banker’s lottery with a number grid. Players staked on integers (often 1–70); the banker drew a number from a bag or box; winning selections paid handsomely but at payoffs far below fair odds, yielding a large house advantage. Biribi teaches two things that feed directly into roulette: (1) numbered stakes invite granular betting strategies (clusters, patterns, “lucky numbers”); (2) a centralized bank can embed advantage by payoff design. Its notoriety was such that it appears in 18th-century bans in both Italy and France. Biribi lacked a wheel—selection was by draw—yet its spirit of numerical wagering against a bank became essential to roulette’s table layout.

Hoca (France/Italy): wheel, ball, and reserved house slots

Hoca (or oca) was a wheel-and-ball banking game with a fixed set of numbered compartments—often cited as around forty-odd—and a subset of house-reserved outcomes. Where Biribi contributed the number grid, Hoca supplied the wheel and ball mechanism plus the notion that certain outcomes belong to the bank. This architecture anticipates roulette’s green 0 (and historically 00): technically “normal” outcomes, but ones for which the bank keeps all outside bets.

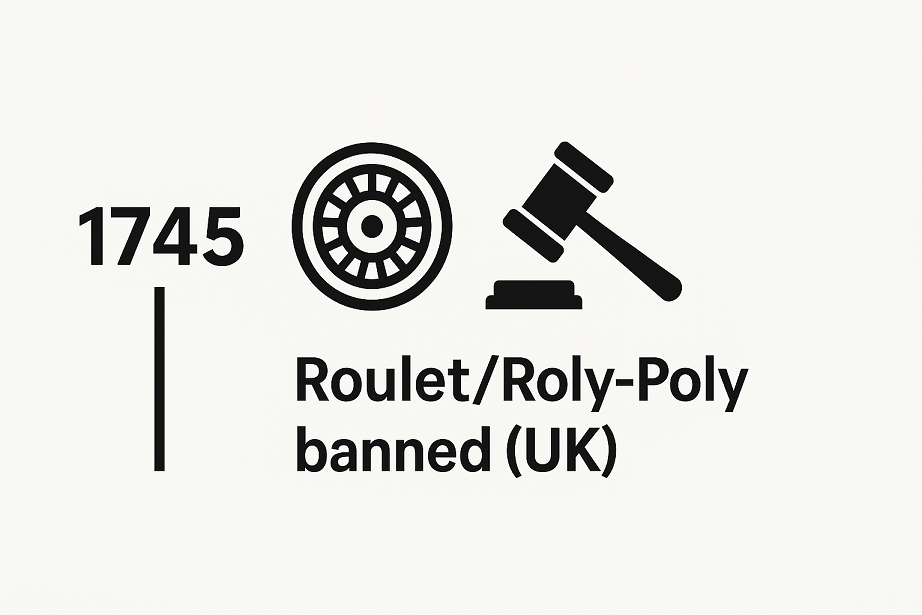

Roly-Poly (“Roulet or Roly-Poly”) in Britain: the legal smoking gun

By the mid-18th century, Britain saw a vogue for wheel games. The Gaming Act of 1745 (18 Geo. II c.34) explicitly bans “Roulet or Roly-Poly,” establishing that a wheel-and-ball, banked game of this family was sufficiently common—and socially disruptive—to merit legislative attention. Contemporary descriptions vary, but the common core is a spinning wheel with alternating colored or marked compartments and “bar holes” (bank pockets) where the house collects all wagers. The semantic coupling “Roulet or Roly-Poly” in legal prose shows that the term roulette was already circulating, even if the modern number layout had not yet stabilized.

Even–Odd (E.O.): binary wagers with bank pockets

Closely related is Even–Odd (E.O.), in which the wheel’s compartments were labeled E or O rather than numbers. Players bet simply on parity; the spinner launched a ball; and if it fell into a bank pocket (a blank or marked “bar”), the house took all. E.O. distilled three roulette fundamentals: (i) a single rotating hardware locus of randomness; (ii) visibly alternating outcomes that invite pattern-seeking; (iii) explicit bank-owned results that generate steady house profit. As crackdowns came, British play cycled among Roly-Poly, E.O., and card-table substitutes, but the appetite for wheel play persisted.

Parisian gaming ecology and regulation

Across the Channel, Paris nurtured a teeming gambling economy despite royal prohibitions. Municipal complaints in the early 18th century mention roulette among disruptive games; later ordonnances list it with Biribi and other jeux de hasard. By the 1790s, the Palais-Royal functioned as a quasi-autonomous commercial zone dense with cafés, arcades, and illicit gaming rooms. It is in this ecosystem that the first modern roulette—numbered pockets with 0 and 00, a full betting tableau of inside and outside wagers, and croupier procedure—surfaces in descriptive sources.

From proto-games to numbers: a synthesis

Viewed structurally, roulette arises by hybridizing two strands: the wheel-and-ball banking game (Roly-Poly/E.O./Hoca) and the number-betting lottery (Biribi). The numbered wheel turns mechanical spectacle into a matrix of granular odds; bank-reserved outcomes translate into the zero pockets; and the betting cloth codifies both traditions into a single instrument. The result—emerging in Paris in the 1790s—is recognizably the game still dealt worldwide.

The Birth of Modern Roulette in France

Lablée’s 1801/02 Testimony

The earliest unambiguous reference to modern roulette comes from Jacques Lablée’s novel La Roulette, ou Histoire d’un joueur, written in 1796 and published in 1801/02. Set in the Palais-Royal in Paris, the book describes a wheel with numbers 1–36 and two additional slots—0 and 00—explicitly reserved for the bank. Lablée also outlines the betting layout: columns, dozens, and even-money wagers on red/black, odd/even, and high/low. This matches the essential structure of the modern roulette game.

What makes Lablée’s testimony so valuable is its detail. Unlike vague mentions in bans or statutes, here we see the full integration of the mechanical wheel with a comprehensive betting system. It is this synthesis—mechanics, mathematics, and social practice—that defines roulette as distinct from its ancestors.

The Palais-Royal as Gambling Hotspot

The Palais-Royal, just north of the Louvre, was a crucible of Enlightenment commerce and vice. By the 1790s it housed cafés, theaters, arcades—and hundreds of illicit gambling rooms. Contemporary reports counted more than 100 gaming salons in operation by 1791. Despite repeated royal and municipal prohibitions, the Palais-Royal’s quasi-legal status (owned by the Duke of Orléans and partly exempt from police intrusion) made it a magnet for gamblers across social classes.

Roulette flourished here because it was easy to learn, offered a range of betting scales (from a single number to broad categories), and promised dramatic swings of fortune. This environment cemented roulette’s identity as the aristocrat of chance games, in contrast to dice or card games often associated with lower classes.

Color Codes and Early Confusion

Interestingly, in these early Parisian wheels the zero and double zero were not green but painted red and black. This created confusion since those colors were also used for even-money bets. To avoid disputes, casinos soon standardized the zeros in green, establishing a global convention still in use today.

From Paris to Prohibition

Despite its popularity, roulette remained technically illegal in France for much of the early 19th century. Police raids shut down some rooms, but the game’s appeal could not be contained. Even when official gambling houses briefly operated under Napoleon, roulette was part of their repertoire. Yet the oscillation between toleration and prohibition would soon shift the center of gravity of roulette away from France—and toward German spa towns.

The Nineteenth-Century Transformation

The Blanc Brothers and the Single-Zero Wheel

A decisive breakthrough came in 1842 at the spa town of Bad Homburg in Germany. François and Louis Blanc, experienced entrepreneurs in the gambling industry, introduced a roulette wheel with only a single zero. This innovation halved the house edge compared to the double-zero wheel, reducing it from 5.26% to 2.7%. The improvement attracted players in droves, giving the Blancs’ establishment a competitive edge over rival casinos still using the traditional layout. The single-zero wheel became synonymous with “French” or “European” roulette and marked the beginning of the modern era of the game.

The Blancs’ reputation was mixed—François had previously been accused of financial manipulations in France—but their genius for exploiting gambling demand was undeniable. By combining better odds with careful marketing, they made Bad Homburg a premier gambling destination in Europe. What was once a modest spa town soon became a magnet for aristocrats, bourgeois travelers, and fortune-seekers alike.

Gambling Bans and Relocation to Monaco

By the 1860s, the political landscape in Germany changed. Governments, concerned about morality and public order, banned gambling outright. This left the Blanc brothers searching for a new haven. Their opportunity arrived when Prince Charles III of Monaco, facing financial strain, invited them to establish a casino. In 1863, the Société des Bains de Mer (SBM) was founded, and by 1865 the Blancs were running the Casino de Monte Carlo. Their crowning achievement was the opening of the grand casino building designed by Charles Garnier, architect of the Paris Opera, in 1878.

Monte Carlo quickly became the global capital of roulette. The single-zero wheel was its showpiece attraction, drawing nobility, wealthy tourists, and adventurers from across Europe and beyond. Revenues from roulette not only enriched the Blanc family but also stabilized Monaco’s finances, transforming the tiny principality into a symbol of gambling luxury.

Myths of the Devil’s Wheel

It was during this Monte Carlo golden age that roulette acquired its sinister nickname: the “Devil’s Wheel.” The reason is a simple numerical curiosity: the sum of numbers 1 through 36 is 666. Superstitious gamblers saw this as proof of the game’s infernal character, and rumors spread that François Blanc had struck a pact with the Devil himself. While such tales have no historical basis, they illustrate the aura of danger, glamour, and fatalism that surrounded roulette in the 19th century.

Roulette as a Symbol of European Aristocracy

By the late 19th century, roulette had become a cultural institution. Monte Carlo’s casino was not only a gaming hall but also a theater of class display: gentlemen in evening dress, ladies in fine gowns, and croupiers in formal attire created a scene of controlled risk and elegance. Stories of gamblers “breaking the bank,” such as the Englishman Charles De Ville Wells in 1891, fed the mythology of the game. Roulette was thus both an economic engine for Monaco and a cultural symbol of European elite sociability.

Roulette in the United States

Arrival in New Orleans

Roulette crossed the Atlantic with French settlers and found its first American home in New Orleans in the early 19th century. The city’s French-Creole culture, combined with its role as a major port, made it a natural entry point for European gambling traditions. By the 1810s, roulette was already established in the city’s gaming houses, alongside other favorites such as faro and dice games.

Spread Along the Mississippi and the Frontier

From New Orleans, roulette spread along the Mississippi River on paddlewheel steamboats. These floating casinos carried the game northward, where it reached river towns and frontier outposts. By the mid-19th century, roulette was a staple in mining camps, saloons, and frontier cities. In contrast to Monte Carlo’s refined salons, American roulette was associated with the rough-and-ready spirit of the frontier and accessible to a much broader social spectrum.

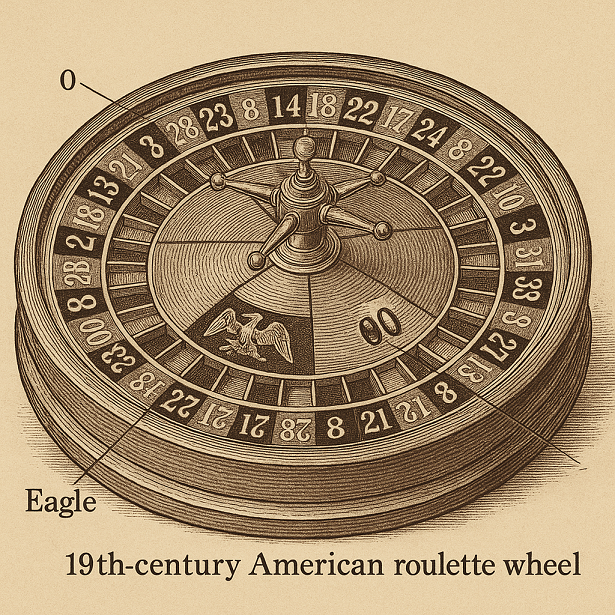

The Double-Zero Standard

While Europe gravitated toward the single-zero wheel after the Blanc brothers’ innovation, the United States retained the double-zero. The American wheel, with its 38 pockets (1–36 plus 0 and 00), established a house edge of 5.26%. This higher edge proved sustainable in an environment with fewer regulatory constraints and less competitive pressure to attract elite patrons. The double-zero wheel became the defining feature of “American roulette” and remains so to this day.

The “Eagle” Pocket Experiment

Some American wheels in the 19th century introduced an additional feature: the “American Eagle” pocket. This was a third house slot, often marked with an eagle symbol, which increased the house edge to nearly 13%. Players disliked the steep odds, and casinos soon abandoned the practice. Nonetheless, it shows the willingness of American gambling houses to experiment with wheel design in pursuit of greater profits.

Adaptations to Prevent Cheating

The rough atmosphere of American gambling halls gave rise to practical innovations. To prevent cheating and hidden devices, operators began mounting roulette wheels on top of tables in plain view, rather than embedded into furniture as in Europe. Betting layouts were simplified to speed up play and reduce disputes. These adjustments created the distinctive style of American roulette: faster-paced, visually open, and with fewer ceremonial trappings than its European cousin.

Twentieth-Century Consolidation

By the early 20th century, roulette had become a fixture of American casinos, though less dominant than craps and blackjack. With the legalization of gambling in Nevada in the 1930s and the rise of Las Vegas, American roulette found its permanent home. The double-zero format, despite its higher edge, became entrenched in U.S. casinos and spread to Latin America and the Caribbean, ensuring a global divide: single-zero in Europe, double-zero in the Americas.

Mathematical and Philosophical Dimensions

Foundations in Probability Theory

Roulette is inseparable from the history of probability. In 1654, Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat exchanged letters on the “problem of points,” laying the groundwork for modern probability theory. Although this was decades before roulette in its modern form, the linkage of games of chance to rigorous mathematics set the intellectual stage. When roulette spread in the 18th and 19th centuries, it became the perfect case study for the new science of risk.

Expected Value and House Edge

Roulette is often cited in textbooks because its payouts are simple to calculate. Consider a straight-up bet on a single number:

- European wheel (37 pockets): Probability of winning = 1/37; payout = 35:1. Expected return = (1/37 × 35) − (36/37 × 1) = −2.7%.

- American wheel (38 pockets): Probability of winning = 1/38; payout = 35:1. Expected return = (1/38 × 35) − (37/38 × 1) = −5.26%.

This arithmetic reveals why the single-zero innovation mattered so much. It nearly halved the casino’s advantage and gave players a more attractive game. On even-money wagers, the difference is similarly stark: −2.7% in Europe versus −5.26% in America.

French Rules: La Partage and En Prison

Some casinos in France added rules that soften the blow when the ball lands on zero:

- La partage: If a player makes an even-money bet and the ball lands on 0, half the stake is returned.

- En prison: If the ball lands on 0, the even-money bet is “imprisoned” for the next spin. If it wins, the stake is returned without profit.

Both rules reduce the house edge on even-money bets from 2.7% to 1.35%, making French roulette the most favorable mainstream variant for players.

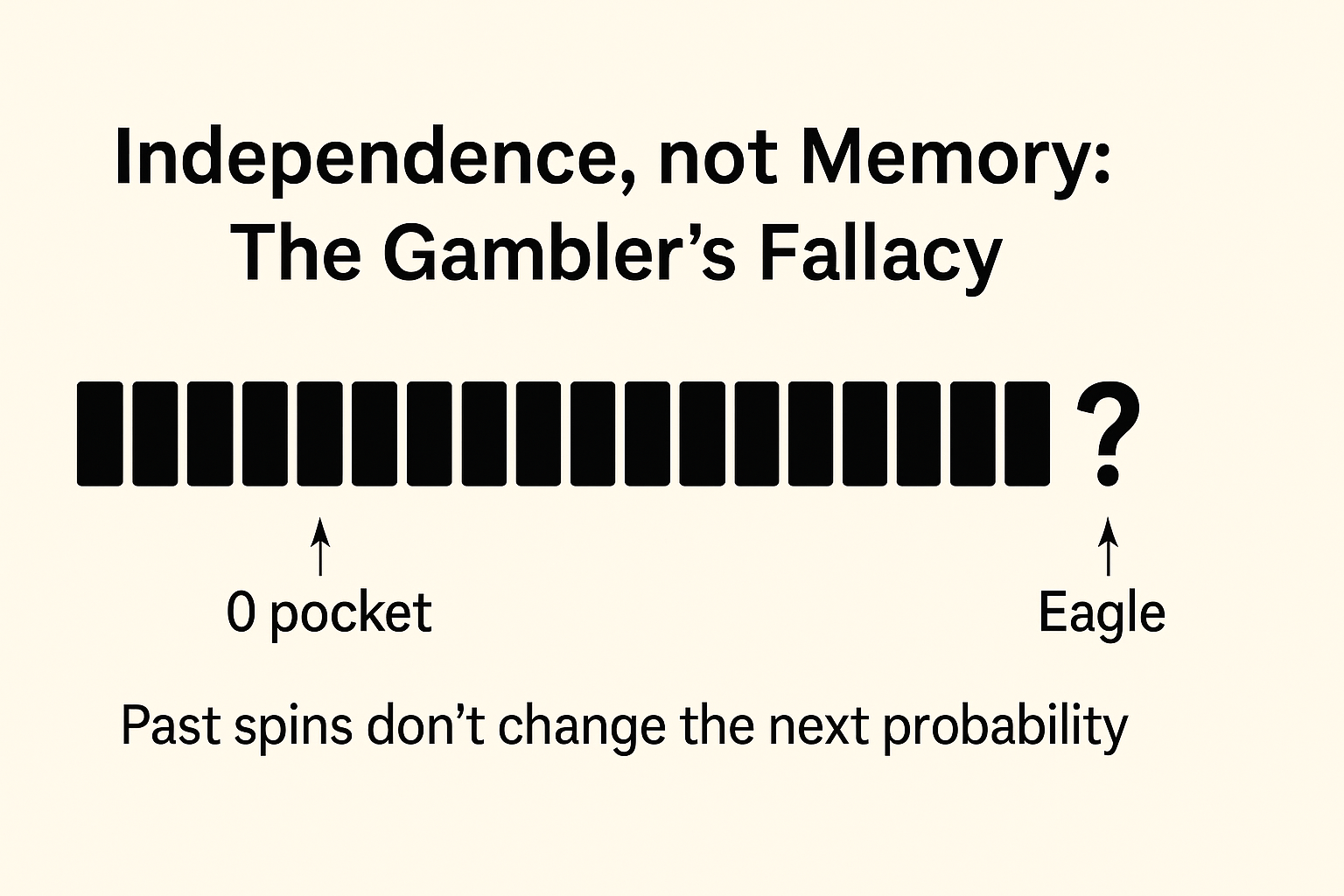

The Gambler’s Fallacy and the Monte Carlo Example

One of the most famous demonstrations of cognitive bias occurred in Monte Carlo in 1913, when the wheel landed on black 26 times in a row. Gamblers, convinced that red was “due,” wagered heavily against black, losing fortunes. This episode illustrates the gambler’s fallacy—the mistaken belief that past outcomes influence future independent events. In reality, the probability of red or black remains constant at each spin, regardless of previous results.

Determinism, Chance, and Physical Prediction

Roulette also raises deeper philosophical questions. On the surface, the wheel appears random; in fact, it is a deterministic physical system. In the 20th century, researchers such as Edward O. Thorp and Claude Shannon built wearable computers that used ball and wheel timings to predict outcomes. Later, physics-based studies confirmed that with precise data, one can forecast sectors of the wheel with a statistical edge. Casinos countered with stricter supervision and more frequent wheel maintenance, ensuring roulette remains functionally random in practice.

Symbolism of the Wheel

Beyond mathematics, roulette resonates with symbolic meaning. Its circular form recalls the medieval “Wheel of Fortune,” turned by the goddess Fortuna to decide human fates. Writers and philosophers have used the spinning wheel as a metaphor for life’s unpredictability: wealth and ruin, joy and despair, hinging on the bounce of a ball. This duality—mathematically precise yet existentially random—explains much of roulette’s cultural allure.

Cultural and Sociological Impact

Roulette in Literature

Few games of chance have inspired as much literary attention as roulette. Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella The Gambler (1866), written under pressure of his own gambling debts, depicts the psychological torment of a man consumed by roulette at a German spa town. The story is both a gripping narrative and a philosophical meditation on compulsion, chance, and freedom. Roulette here is not just entertainment but a mirror of the human condition.

Other 19th-century memoirs and novels mention roulette as a fashionable pastime in Paris, Baden-Baden, Wiesbaden, and Monte Carlo. The wheel becomes a recurring symbol of risk and fate, a shorthand for both glamorous living and reckless ruin.

Visual Arts and Symbolism

Roulette tables appeared in paintings, engravings, and caricatures of the 19th century. Artists often portrayed elegant ladies and gentlemen gathered around the wheel, capturing the atmosphere of high society. Satirical prints emphasized the destructive lure of gambling, contrasting the elegance of the salon with the despair of the loser. The wheel, circular and inexorable, became an artistic metaphor for the cycles of fortune.

Roulette in Film

In the 20th century, roulette moved onto the silver screen. The most famous cinematic scene is in Casablanca (1942), where Humphrey Bogart’s character helps a young couple by secretly rigging the wheel in their favor. The moment immortalized roulette as a moral stage, where fate could be bent for compassion. In the James Bond franchise, roulette tables appear repeatedly, cementing their association with elegance, espionage, and risk.

Public Morality and Regulation

Roulette has always been politically contested. In France, it was alternately tolerated and banned depending on the regime. In Germany, it was driven out in the 1860s as governments embraced moral reform. In Britain, statutes against “Roly-Poly” and roulette reflect long-standing anxieties about gambling’s social impact. Across the Atlantic, the United States allowed roulette to flourish in unregulated frontier conditions, but formal casinos later came under state supervision. The oscillation between prohibition and legalization shows how roulette has been a litmus test for society’s attitudes toward chance and vice.

The Online Revolution

In the late 1990s, roulette entered the digital age. Online casinos began offering both RNG (random number generator) versions and, later, live dealer streams. Players could watch a real wheel via video link and place bets remotely, recreating the experience of the casino at home. Digital variants proliferated: multi-ball roulette, mini-roulette with only 13 numbers, and novelty versions with multipliers or bonus features. Despite these innovations, the core design—a wheel, a ball, and a betting cloth—remains unchanged, proving the timeless appeal of the game.

Roulette as Cultural Icon

Today, roulette is more than just a casino game: it is a global symbol of gambling itself. The red and black pockets evoke the thrill of risk in advertising, films, and even everyday expressions (“to spin the wheel,” “life is roulette”). Its endurance across centuries demonstrates the game’s unique combination of mathematical elegance, sensory drama, and cultural resonance. Whether in the chandeliers of Monte Carlo, the neon of Las Vegas, or the virtual lobbies of online casinos, roulette continues to embody the human fascination with chance.

Conclusion

Roulette’s history is both complex and captivating. What began as a hybrid of wheel games like Roly-Poly and number lotteries like Biribi crystallized in late 18th-century Paris into the roulette we know today. Its subsequent evolution shows a game adapting to the demands of economics, politics, and culture: the single-zero wheel pioneered by the Blanc brothers in Germany, the glamour of Monte Carlo, the double-zero wheel entrenched in the United States, and the experimental variations that came and went.

Mathematically, roulette illustrates the concept of expected value and the inevitability of the house edge, yet psychologically it remains fertile ground for biases like the gambler’s fallacy. Culturally, it symbolizes both elegance and risk, inspiring literature, art, and film. Today, with online casinos, roulette is accessible worldwide, yet its essential format has barely changed for more than two centuries.

In short, roulette endures because it embodies the paradox of gambling itself: a mathematically predictable system that feels endlessly unpredictable to the human heart.

FAQs

Who invented roulette?

Roulette does not have a single inventor. The game emerged in 18th-century France, influenced by earlier games like Roly-Poly, Even–Odd, Biribi, and Hoca. The first clear description of modern roulette comes from Jacques Lablée’s 1801/02 book, which mentions 0 and 00 as house slots.

Why is roulette called the “Devil’s Wheel”?

Because the sum of the numbers 1 through 36 equals 666, the biblical “Number of the Beast.” This coincidence led to the nickname, though it was never an intentional design choice.

What’s the difference between European and American roulette?

European roulette uses a single-zero wheel with 37 pockets and has a house edge of about 2.7%. American roulette uses a double-zero wheel with 38 pockets and a house edge of 5.26%. French rules like la partage further reduce the edge to 1.35% on even-money bets.

What was the 1913 Monte Carlo fallacy incident?

In 1913, a roulette wheel in Monte Carlo landed on black 26 times in a row. Gamblers assumed red was “due” and lost heavily, illustrating the gambler’s fallacy—the false belief that past outcomes influence future independent events.

What about modern variations?

Casinos occasionally experiment with new formats. Some American wheels once had an extra “Eagle” pocket, and in the 2010s triple-zero wheels appeared in Las Vegas. Online casinos now offer multi-ball and mini-roulette variants, but the classic wheel remains the standard worldwide.

Sources

- Jacques Lablée, La Roulette, ou Histoire d’un joueur (Paris, 1801/02).

- British Parliament, Gaming Act of 1745 (18 Geo. II c.34).

- Richard A. Epstein, The Theory of Gambling and Statistical Logic, 2nd ed. (Academic Press, 2009).

- Encyclopædia Britannica, “Roulette.”

- Michael Small & C.K. Tse, “Predicting the outcome of roulette,” Chaos, American Institute of Physics, 2012.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Gambler (1866).

- Wizard of Odds, “Roulette Rules, Odds, and Strategy.”

- Thierry Depaulis, research on French gambling in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Official history of the Société des Bains de Mer (Monaco).