Long before the grandeur of the pyramids and the mystique of Senet captivated the imagination of ancient Egypt, there existed a game of spiraling mystery and divine protection: Mehen. Carved in the shape of a coiled serpent, this extraordinary board game is one of humanity’s oldest known forms of strategic entertainment, with archaeological evidence stretching back to the predynastic period—before 3100 BCE. The name “Mehen” itself invokes the protective snake deity who coiled around the sun god Ra’s boat each night, shielding him from the chaos serpent Apophis during his perilous journey through the underworld. This was not merely a pastime; it was a physical manifestation of cosmic order, a ritual reenactment of divine protection played out on stone and clay. Yet despite its profound cultural significance and widespread presence in the tombs of Egypt’s elite during the Old Kingdom, Mehen vanished from history as mysteriously as it appeared, leaving behind only silent boards and tantalizing fragments of its rules. This article delves into the history of the ancient Egyptian game Mehen, tracing its origins, symbolism, gameplay theories, and the enigmatic circumstances of its disappearance.

The Ancient Origins of Mehen

The story of Mehen begins in the shadowy dawn of Egyptian civilization, in the predynastic era when the foundations of one of the world’s greatest cultures were being laid. The earliest known Mehen boards date to approximately 3000 BCE, contemporary with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaohs of the 1st Dynasty. These are not simple gaming artifacts; they are sophisticated works of art, typically carved from limestone, alabaster, or other fine stone, meticulously shaped into the form of a coiled serpent with a spiral track winding from the tail at the outer edge to the head at the center.

Archaeological excavations have unearthed Mehen boards at prestigious sites throughout Egypt, including the royal cemeteries of Abydos, Saqqara, and Helwan. The care with which these boards were crafted and their placement within elite tombs—often alongside other precious grave goods—speaks volumes about the game’s importance. This was a game for the upper echelons of society, a marker of status and sophistication. The spiral itself, consisting of anywhere from 50 to over 400 segments or “houses” depending on the board’s size, represents one of the most distinctive game designs in the ancient world. No other culture of that era created anything quite like it, making Mehen a uniquely Egyptian phenomenon and a testament to the civilization’s early capacity for abstract symbolic thinking.

The Serpent God: Religious and Cultural Symbolism

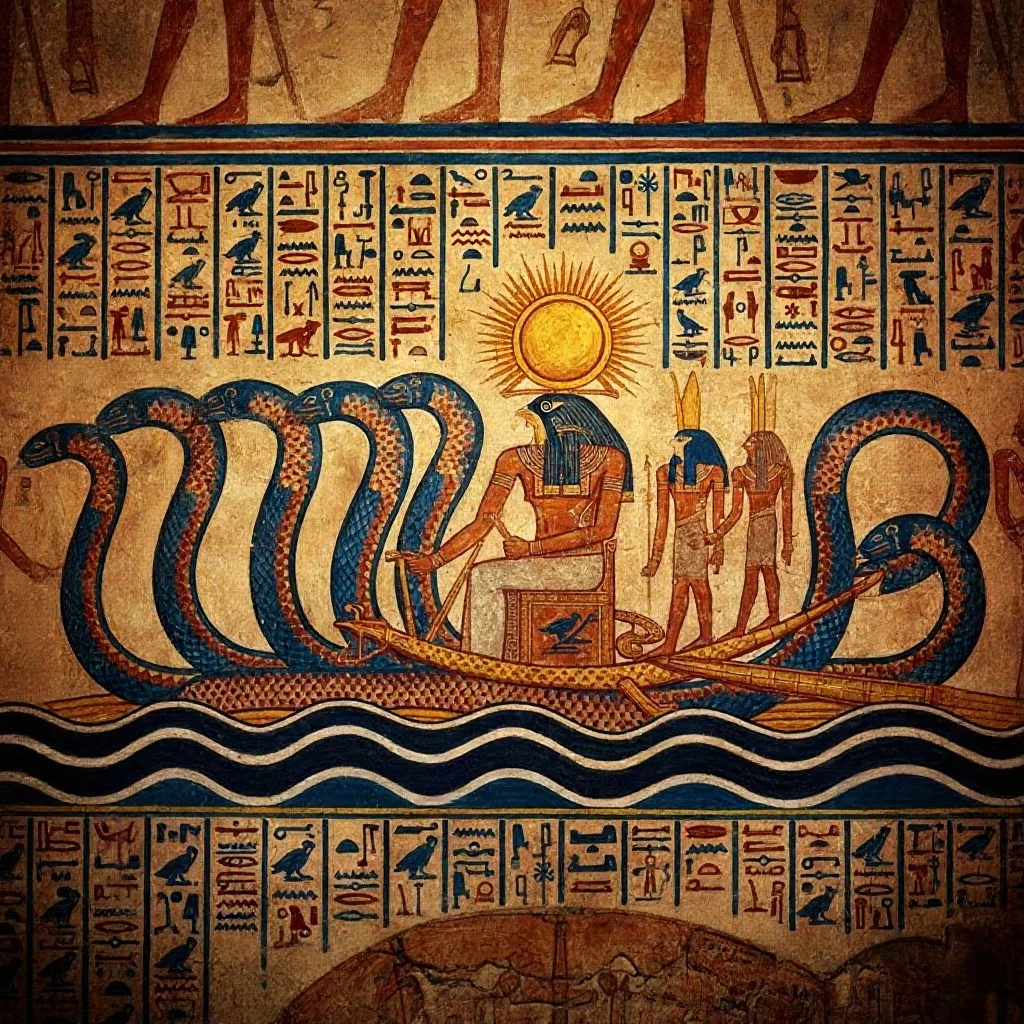

To understand Mehen the game, one must first understand Mehen the deity. In Egyptian mythology, Mehen was the “Enveloper” or “Coiled One,” a massive serpent who wrapped himself protectively around Ra’s solar barque during the twelve perilous hours of night. Each evening, the sun god would descend into the Duat (the underworld), where he faced innumerable threats, chief among them the chaos serpent Apophis who sought to devour him and plunge the world into eternal darkness. Mehen’s coils formed an impenetrable defensive barrier, a living shield that ensured Ra’s safe passage and the sun’s triumphant rebirth each dawn.

The game board’s spiral design is a direct physical echo of this divine coiling. Players racing their pieces from the outer tail to the inner head were symbolically enacting the journey through danger toward safety and ultimate triumph—a microcosm of the cosmic struggle between order (Ma’at) and chaos (Isfet). The number of segments on many Mehen boards may have held numerological significance, possibly relating to hours of the night, days of sacred calendars, or other ritual timekeeping systems that governed Egyptian religious life.

This deep religious symbolism made Mehen more than entertainment; it was a ritual object, a tool for aligning oneself with divine protection. The game’s presence in tombs suggests that the deceased might “play” it in the afterlife, perhaps using it as a guide or safeguard during their own perilous journey through the underworld. The connection between gameplay and spiritual protection is a recurring theme in ancient Egyptian gaming culture, seen also in Senet, where the race across the board mirrored the soul’s journey to the Field of Reeds.

Archaeological Evidence and Material Culture

The physical evidence for Mehen is both abundant and frustratingly incomplete. Dozens of Mehen boards have been recovered from 1st through 6th Dynasty contexts (approximately 3000–2200 BCE), with the vast majority coming from the early Old Kingdom. These boards vary considerably in size, from compact examples measuring 20 centimeters in diameter to massive specimens exceeding 50 centimeters. The spiral track is sometimes incised directly into the stone surface, while in other examples, small depressions or drilled holes mark each “house” along the serpent’s body.

Accompanying these boards are sets of game pieces that add layers of intrigue to the reconstruction puzzle. Two distinct types of playing pieces have been found in association with Mehen boards: small spherical marbles (typically made of stone, ivory, or faience) and carved lion figurines. A typical set might include three to six lions per player and a corresponding number of marbles. The lions, often exquisitely detailed despite their miniature scale, range from simple geometric forms to naturalistic sculptures showing the king of beasts in a resting or walking pose. The presence of lions—symbols of royal power and solar divinity closely associated with pharaohs—reinforces the game’s connection to elite culture and divine mythology.

One particularly significant find comes from the tomb of Hesy-Ra at Saqqara (3rd Dynasty, circa 2650 BCE), where a complete Mehen set was discovered alongside other luxury goods. The board itself was carved from fine limestone with remarkable precision, and the accompanying lion pieces were fashioned from ivory. Such discoveries confirm that Mehen was not a casual diversion but a valued possession worthy of accompanying the deceased into eternity.

Reconstructing the Lost Rules

Here we encounter one of archaeology’s most tantalizing mysteries: not a single ancient Egyptian text explicitly describes how to play Mehen. Unlike Senet, which appears in tomb paintings showing players in action and has some textual references, Mehen exists only as silent artifacts. This absence has not deterred modern scholars, who have constructed several competing theories based on the physical evidence and comparisons with other ancient race games.

The most widely accepted reconstruction suggests that Mehen was a multi-player race game, likely accommodating two to six players. Each player would control a set of pieces—probably the marbles, with the lion figurines serving as a special “master” piece or perhaps a blocking element. The objective was to race from the tail (outer edge) of the spiral to the head (center), navigating the coiled track space by space. Movement would have been determined by some randomizing mechanism, possibly throwing sticks (similar to those used in Senet) or perhaps knucklebones, though no dice have been definitively associated with Mehen finds.

The dual nature of the game pieces—both marbles and lions—suggests a two-tiered gameplay mechanic. One theory proposes that players first raced their marbles to the center, and only after achieving this could they introduce their lion piece, which would then race outward from center to tail, “hunting” opponents’ marbles or blocking their progress. This would create a dynamic where early leaders become targets, and strategic positioning becomes as important as speed. Another theory suggests the lions were protective pieces that moved alongside the marbles, defending them from capture by opponents.

The capture mechanism, if any existed, remains purely speculative. Some reconstructions propose that landing on an occupied space allows capture (similar to the Royal Game of Ur), while others suggest a more cooperative race with minimal interaction between players. The spiritual significance of reaching the serpent’s head—the seat of divine protection—would have made victory symbolically potent, representing one’s successful navigation through life’s dangers under the protection of the gods.

The Enigmatic Disappearance of Mehen

As suddenly as Mehen appeared in the archaeological record, it vanishes. After flourishing throughout the early Old Kingdom (Dynasties 1–6), the game disappears almost entirely by the end of the 6th Dynasty, around 2200 BCE. No Mehen boards have been found in Middle Kingdom contexts or later periods, and the game is never mentioned in any surviving texts from subsequent eras. For a game that had been ubiquitous among the elite for nearly 800 years, this abrupt cessation is remarkable and demands explanation.

Several theories attempt to account for Mehen’s disappearance, each reflecting broader changes in Egyptian society and religion during the turbulent transition from the Old Kingdom to the First Intermediate Period. One hypothesis centers on religious transformation. The collapse of centralized power at the end of the Old Kingdom brought significant shifts in religious practice and belief. The solar theology that dominated the Old Kingdom—with its emphasis on Ra’s nightly journey and the protective role of deities like Mehen—may have waned in favor of other religious currents, particularly the rising prominence of Osiris and his underworld realm. As the mythological framework that gave Mehen its meaning shifted, the game itself may have lost relevance.

Another possibility involves the rise of competing games. The Middle Kingdom saw Senet achieve even greater popularity and cultural penetration than it had enjoyed previously. Senet’s flexibility, its association with multiple deities, and perhaps its more engaging gameplay may have simply supplanted Mehen. Similarly, Aseb (the Game of Twenty Squares), which had Mesopotamian origins but was played in Egypt, might have offered a fresh alternative that captured players’ imaginations.

A third theory suggests that Mehen’s disappearance reflects changing burial customs and material culture rather than the game actually ceasing to be played. Perhaps the game transitioned from expensive stone boards to perishable materials like wood or painted cloth that have not survived archaeologically. However, the complete absence of any later textual references makes this explanation less satisfying. When Egyptians of the New Kingdom wanted to reference ancient games, they mentioned Senet extensively—but never Mehen.

Mehen’s Legacy and Modern Reconstructions

Despite its ancient extinction, Mehen has experienced a modern resurrection. Museums worldwide that house Egyptian collections—including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo—display Mehen boards as prized examples of early gaming culture. These silent serpents continue to fascinate visitors, their elegant spiral form a testament to the aesthetic sensibilities of humanity’s earliest civilizations.

Game historians and enthusiasts have created numerous reconstructed rule sets, each an educated hypothesis about how this ancient game might have been played. While we may never know the true rules with certainty, these modern versions allow contemporary players to experience something of what an Egyptian noble might have felt 5,000 years ago, moving pieces along the coils of the protective serpent, racing toward the safety of the divine head. Some reconstructions have been published in academic works on ancient games, while others circulate in the board game hobbyist community, keeping the spirit of Mehen alive even as its original form remains elusive.

The game also serves as a valuable teaching tool, offering insights into Egyptian religious thought, social structures, and the universal human desire for play. When viewed alongside other predynastic Egyptian games, Mehen helps paint a picture of a society already sophisticated in its leisure pursuits, already thinking symbolically and abstractly about competition, chance, and cosmic order.

Mehen in Context: Egypt’s Gaming Culture

Mehen did not exist in isolation. It was part of a vibrant gaming culture in ancient Egypt that included several distinct traditions. While Senet became the most famous and enduring of Egyptian board games, surviving for over 3,000 years and appearing in countless tomb paintings and religious texts, Mehen represents an earlier chapter in this story. The fact that elite Egyptians of the Early Dynastic Period invested time and resources into creating elaborate game boards demonstrates that structured leisure and symbolic play were valued from the very beginning of pharaonic civilization.

The relationship between Mehen and other games remains unclear. Did families own multiple game boards, switching between Mehen and Senet depending on mood or occasion? Were certain games associated with specific festivals or religious observances? The archaeological record suggests that gaming was a regular feature of elite life, with tomb assemblages sometimes including multiple different game types. This parallels the gaming culture of other ancient civilizations—Mesopotamian nobles played both the Royal Game of Ur and various dice games; Romans enjoyed everything from dice (tesserae) to complex board games.

What makes Mehen particularly special is its unique visual identity. The spiral serpent board is instantly recognizable and unlike any other gaming artifact from the ancient world. It stands as a powerful reminder that each culture develops its own symbolic vocabulary for play, embedding local beliefs, aesthetics, and values into even the most recreational activities. The coiled snake of Mehen is as distinctly Egyptian as the hieroglyphic script or the pyramids themselves.

Conclusion

Mehen remains one of the great enigmas of ancient gaming—a beautifully crafted artifact of profound religious significance whose rules have been lost to time, yet whose cultural importance is undeniable. From its origins in predynastic Egypt through its flourishing in the Old Kingdom and its mysterious disappearance, the Mehen board game history offers a window into the minds of some of humanity’s earliest civilizations. These ancient Egyptians did not simply struggle for survival; they created art, worshipped gods, built monuments, and played games that expressed their deepest beliefs about protection, journey, and cosmic order.

The spiral track of the serpent deity, winding from danger at the periphery to safety at the divine center, encapsulates a worldview in which life itself was understood as a perilous journey requiring divine protection. Every game of Mehen played in an ancient Egyptian home or palace was both entertainment and ritual, both competition and prayer. Though we may never roll the dice (or throw the sticks) exactly as they did 5,000 years ago, the silent stone serpents in museum displays continue to speak to us across the millennia, reminding us that the human impulse to play—to create meaning through structured competition—is as old as civilization itself. Mehen may have vanished from living memory in antiquity, but its rediscovery ensures that this earliest of games has achieved a form of immortality its creators would surely have appreciated.

FAQs

- What is Mehen?

- Mehen is an ancient Egyptian board game dating back to approximately 3000 BCE, before the construction of the pyramids. It is characterized by its distinctive spiral shape, designed to resemble a coiled serpent. The game board represents the protective snake deity Mehen, who guarded the sun god Ra during his nightly journey through the underworld.

- How old is the Mehen game?

- Mehen is one of the oldest known board games in human history, with archaeological evidence placing it in the predynastic and Early Dynastic periods of Egypt, around 3000 BCE. This makes it contemporary with the very first pharaohs and the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. The game remained popular throughout the Old Kingdom (approximately 2686–2181 BCE) before mysteriously disappearing.

- How was Mehen played?

- The exact rules of Mehen have been lost to history, as no ancient Egyptian texts describe its gameplay. Modern scholars have reconstructed possible rules based on the physical evidence: it was likely a multi-player race game where players moved pieces (marbles and lion figurines) along the spiral track from the tail to the head (center). Movement was probably determined by throwing sticks or knucklebones, and the game may have involved strategic blocking or capturing of opponents’ pieces.

- Why did Mehen disappear?

- Mehen vanished from the archaeological record around 2200 BCE, at the end of the Old Kingdom. Theories for its disappearance include: changes in religious beliefs that diminished the importance of the Mehen serpent deity; the rising popularity of competing games like Senet; or shifts in burial customs that meant the game was no longer included in tombs. The collapse of centralized authority during the First Intermediate Period brought profound cultural changes that may have rendered this ancient game obsolete.