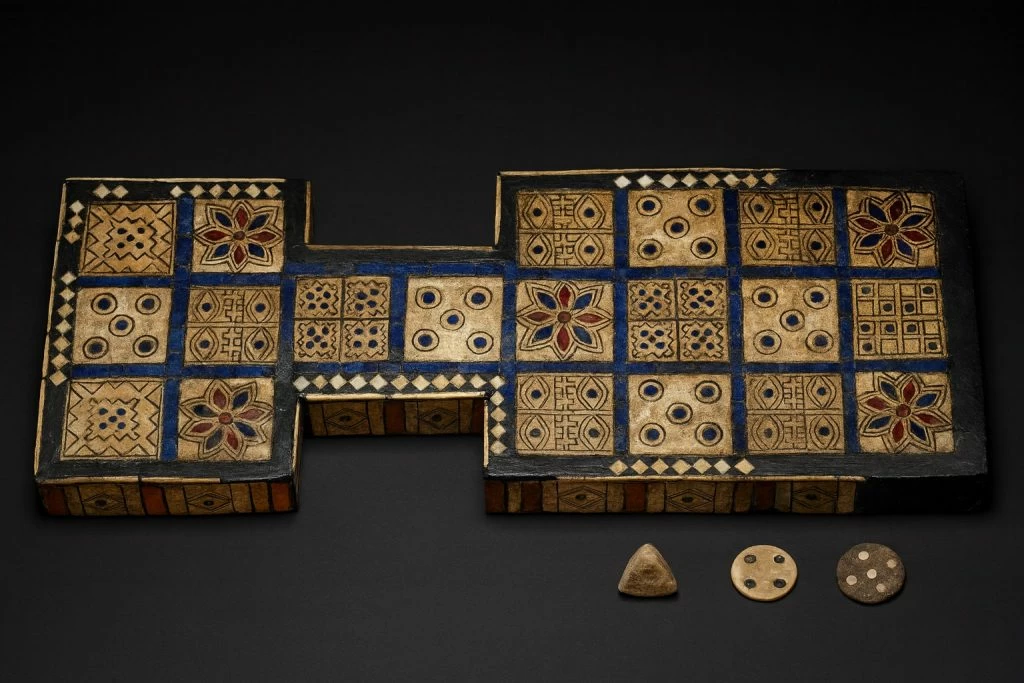

The Royal Game of Ur is a Sumerian board game that belongs to the broader family of ancient Middle Eastern games commonly known as the Game of Twenty Squares. This particular version was unearthed by Sir Leonard Woolley during his 1926–1927 excavations of the Royal Tombs of Ur in modern-day Iraq. It dates back to around 2500 BCE. One of the most famous surviving game boards is currently housed in the British Museum (catalog number: 1928,1009.379.a).

Reconstructing Ancient Rules

While the original rules have not survived, scholars have attempted to reconstruct the gameplay using a cuneiform tablet discovered in 1880. This tablet, authored by the Babylonian scribe Itti-Marduk-balāṭu around 177–176 BCE, is now part of the British Museum’s collection (inventory: Rm-III.6.b – 33333B). Despite its Babylonian origin, the tablet provides insight into how a similar race game might have been played.

However, many reconstructions—such as those by R.C. Bell and Irving Finkel—have been criticized for producing a slow-paced and unengaging game. Given the widespread archaeological finds of similar boards across the Mediterranean and Middle East, it’s clear the game had lasting appeal. Hence, it’s likely that gameplay was more strategic and dynamic than early rule reconstructions suggest.

Boards found at Jiroft, Shahr-i Sokhta, and Egyptian Aseb share a similar layout of 20 squares but often lack the distinctive cell markings of the Royal Game of Ur. This strongly indicates that while structurally similar, these versions followed different gameplay mechanics.

A Modern Take: Dmitriy Skiryuk’s Rule Set

Dmitriy Skiryuk, a Russian game historian and reconstructor, proposed a refined and highly strategic version of the game. His interpretation emphasizes cell markings, unique piece behavior, and tactical play. Here’s an overview of his approach:

Components

- 2 Players

- 1 Game board with 20 marked squares

- 7 white and 7 black pieces, each with one dotted side and one blank side

- 3 tetrahedral dice (4-sided) with two corners painted differently

Dice Mechanics

- 1 colored tip up = score of 1

- 2 colored tips up = 2

- 3 colored tips up = 3

- 0 colored tips up = 4 (maximum score)

- Players may roll only once per turn

- The game begins when a player rolls a 1

Game Setup and Movement

- All pieces begin off the board.

- The starting piece enters at C4 (White) or A4 (Black) when a score of 1 is rolled.

- Pieces are introduced onto the board corresponding to dice results:

- Score 1 → C4/A4

- Score 2 → C3/A3

- Score 3 → C2/A2

- Score 4 → C1/A1

Movement Path

- White and Black follow mirrored routes across the board, starting from opposite sides and converging at the central track.

- A piece may only move forward along its designated path.

- If a move is possible, the player must make it; otherwise, the turn is skipped.

- The blank side faces up when entering; pieces flip to the dotted side upon reaching B8 (the central cell).

Combat and Interaction

- Capture Rules:

- Pieces can knock off an opponent’s piece only if both are on the same side (blank vs. blank or dotted vs. dotted).

- A piece cannot capture if it’s on a “safe cell” or if the opponent’s piece is part of a stack.

- Safe Zones and Stacking:

- Rosettes (A1, C1, B4, A7, C7): Grant an extra turn when landed on. A player may move any piece for that bonus turn.

- 4-Eye Cells (A2, C2, A4, C4, B7): Allow stacking of up to 4 pieces from the same player. B7 acts as a “gateway” cell for the central track, preventing gridlock.

- Four 5-Dot Sets (B3, B6): Universal safe zones. Any combination of pieces can stack here, regardless of ownership or orientation.

- Single 5-Dot Cells (A8, C8): Transitional cells. Pieces must leave this space and cross B8 to flip sides.

- Final Cell – B1 (12 Dots):

- The game’s end point and a safe cell—but only for dotted pieces.

- Cannot be stacked; only one piece may occupy it at a time.

Exiting the Board

To exit the board, a piece must reach one of the final four cells and roll the exact number:

- B1 → 1

- B2 → 2

- B3 → 3

- B4 → 4

Knocked-off pieces restart from scratch. The goal is to successfully exit all 7 pieces.

Strategic Considerations

- Starting Fairness: Only allowing play to begin on a roll of 1 balances early-game progression.

- Rosette Dilemma: While extra turns are powerful, remaining stationary on Rosettes may lead to congestion.

- Flipping Mechanism at B8: This acts as a strategic bottleneck. Since a piece can’t be flipped mid-cell, players may delay movement to control positioning and block opponents.

- Stack Limit: The 4-piece cap is both a physical and tactical constraint, encouraging thoughtful staging.

- Traffic Jam Dynamics: Players can intentionally block paths at key junctions, especially near Rosettes or B8, introducing layers of positional control.

- Final Cell Protection: Prevents frustration at the last moment and reflects similar endgame protections in other ancient games like Senet.

The Royal Game of Ur, especially in Skiryuk’s version, presents a rich combination of luck, tactics, and positional awareness. Far from being a mere race game, it offers complexity through unique cell behaviors, combat rules, and strategic depth—explaining why it captivated players for centuries.

Would you like a printable ruleset, a visual game board reference, or digital version for play?